advanced go & gamedev

go quirks & tricks

starting software

In this article, we’ll cover how and why to build a fully-featured debug console that allows live editing of a program’s state, such as:

and much more.

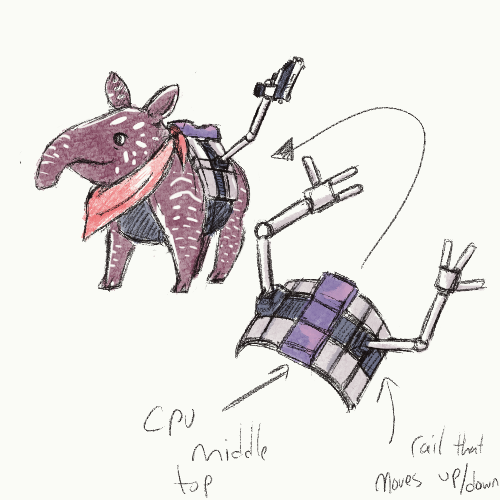

For the last few months I’ve been working nearly full-time on my own 2D Game, ‘Tactical Tapir’, a top-down shooter a-la Nuclear Throne.

Some concept art from the excellent Brian Mulligan:

some in-game art (also by Brian):

Unlike most games, I’m not using a conventional engine: it’s almost all hand-written Go code, using [ebiten](https://ebiten.org/) to sit between my code & the GPU and do some input handling. Working with games is a new domain for me: systems are not as isolable as they are in web development or device drivers. In some ways, the questions game development asks are much more subjective: instead of asking “is this code correct?”, you ask “does this feel nice?” “Testing” games is very different rather from say, a web server: you have ‘squishy’, subjective requirements like ‘does this feel nice?’ or ‘is this fun?’ rather than ‘does this code meet the spec?’. There’s no spec for fun, at least as far as I know.

That is, I need to answer questions like this:

To accomplish that, I’ll need to be able to quickly and easily:

This is actually pretty easy in an interpreted language like LUA or Python, but tricky or impossible in a some compiled languages. Luckily, Go’s powerful suite of reflection tools makes this possible.

Before we get into the console, let’s talk about Game development in general and the process that led to me making a console.

A game is a program that runs in a loop. Each update, or frame, does the following:

That is, our game loop should look like this:

for tick := 0; ; tick++ {

inputs := input.ThisFrame()

debugUpdate(game, inputs)

if err := game.Update(inputs, tick); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("shutdown: update(): %v")

}

if err := game.Draw(screen); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("shutdown: draw(): %v")

}

}

I started by adding individual keyboard-triggered cheats to the game.

We’ll use keyboard inputs to trigger the cheats. We don’t want the player to trigger them accidentally, so we’ll require that they hold down the shift and ctrl keys while pressing H and A respectively.

func applyCheats(g *Game, input Inputs) {

if input.Held[KeyShift] && input.Held[KeyCtrl] {// check for cheats: if no ctrl+shift, no cheats

if input.JustPressed[KeyA] {

log.Println("infinite ammo")

g.Player.Ammo = math.Inf(1)

}

if input.JustPressed[KeyH] {

log.Println("infinite health")

g.Player.HP = math.Inf(1)

}

}

}

Which makes our game loop look like this, checking and applying cheats before each update:

func (g *Game) Update(input Inputs) {

for tick := 0; ; tick++ {

inputs := input.ThisFrame()

applyCheats(game, inputs)

debugUpdate(game, inputs)

if err := game.Update(inputs, tick); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("shutdown: update(): %v")

}

if err := game.Draw(screen); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("shutdown: draw(): %v")

}

}

This works pretty well. In fact, we can visualize it as a kind of table:

| cheat | key | description |

|---|---|---|

| ∞ ammo | ctrl+shift+A |

set State.Player.Ammo to math.Inf(1) |

| ∞ hp | ctrl+shift+H |

set State.Player.HP to math.Inf(1) |

Which naturally suggests using a map to store the cheats:

var cheats map[Key]struct {

description string

apply func(*Game)

} {

KeyA: {

description: "spawn ammo",

apply: func(g *Game) {

g.Pickups = append(g.Pickups, AmmoPickup{...})

},

},

KeyH: {

description: "spawn health",

apply: func(g *Game) {

g.Pickups = append(g.Pickups, HealthPickup{...})

},

},

}

func applyCheats(g *Game, input Inputs, cheats map[Key]struct {

description string

apply func(*Game)

}) {

if input.Held[KeyShift] && input.Held[KeyCtrl] {// check for cheats: if no ctrl+shift, no cheats

for key, cheat := range cheats {

if input.JustPressed[key]

log.Println(cheat.description)

cheat.f(g)

}

}

}

While this works well for some tasks, a few limitations are immediately apparent:

For some things, like ‘infinite HP’, this is fine. But for other things, like ‘exactly 28 HP’, this is absurd. You’d either need to write a function for every possible value, or expand the system somehow to take arguments. We need a more general approach.

The default API for general-purpose inputs is the command line. That is, prompt that takes a line of text, parses it as a command, and executes it.

The TacticalTapir console has two layers: the terminal, which takes user input and translates it into lines of text, and the shell, which parses those lines of text into commands and executes them.

That is, every frame, we’ll UpdateTerm() until the user hits enter, then we’ll ParseCommand() and Exec() that command, updating the gamestate as necessary.

Additionally, every frame, we’ll UpdateState based off of the current gamestate and preivious Commands.

Additionally, we’d like to generate completions for the user as they type - we’ll get to that later.

// A debug console that allows you to inspect and modify the game state at runtime.

// It's accessed by pressing ~ (shift+`).

// Create one with New(), passing in a pointer to the root of the struct you want to inspect. Call Update() every frame with a pointer to the same value and the current input.Keys

// to see if you got a *Command, then Exec() it to modify the gamestate.

type Console struct {

State // State of the game modified or watched by the console.

Terminal // Terminal state: input, history, etc; never touches the game state.

Completions // Possible completions for the current line.

}

A basic terminal includes the following navigational features:

| key(s) | description | gif |

|---|---|---|

'a'..'z' or other printable characters |

insert the character at the cursor |  |

← and → |

move the cursor left and right |  |

⇧ + ←, ⇧ + → |

move the cursor left and right a word |  |

⌫ |

delete the character to the left of the cursor |  |

⇧ + ⌫ |

delete a word to the left of the cursor |  |

␡ |

delete the character to the right of the cursor |  |

⇧ + ␡ |

delete a word to the right of the cursor |  |

↑ and ↓ |

navigate the history, if there is one: they don’t wrap. |  |

⇧ + ↑ and ⇧ + ↓ |

go to the start and end of the history. |  |

⌤ (enter) |

submit the current line of text | SEE BELOW |

↹ (tab) |

autocomplete the current line of text |  |

Working backwards, we’ll need to keep track of the following:

Additionally, there are a few gotchas we’d like to avoid:

As a Go struct, this looks like:

// Terminal is the state of the current text input; i.e, the cursor, current line, suggested completion, etc.

// Call CurrentLine(), Cursor(), and SuggestedCompletion() to get read-only views of the current line, cursor position, and suggested completion to

// emulate a terminal for it.

type Terminal struct {

history History

historySave struct {

time time.Time

prev History

sync.Mutex

}

curLine string // current line of (normalized) input. View from outside with CurrentLine()

curLineRunes []rune // runes to append to curLine: reusable buffer to avoid extra allocations

cursor int // c.cursor position in curLine. View from outside with Cursor().

lastNavigationRepeat time.Time // time of last navigation repeat

suggestedCompletion string // suggested completion for curLine. View from outside with SuggestedCompletion().

}

Each frame, we’ll UpdateTerm(&term, keys) with the state of the terminal and the current input, and DrawTerm to render it to the screen. (Drawing is outside the scope of this article, though - I hope to get to it soon!)

Before we get to the implementation, let’s quickly go over the API for the input.Keys type. The ebiten.Key type represents a physical key on a 109-key ANSI keyboard, the most common keyboard layout in the US. Other layouts exist, but we’re O.K. with dropping the few bonus keys on, say, the JIS layout.

We’d like an API that looks like this:

package input // input/input.go

type Keys struct { /* some fields */ }

// Pressed starting this frame.

func (k Keys) Pressed(ebiten.Key) bool {}

// Released starting this frame

func (k Keys) Released(ebiten.Key) bool {}

// Continuously held down; either pressed this frame or continuing from a previous frame.

func (k Keys) Held(ebiten.Key) bool {}

I.E, if on five frames we got the following inputs for the letter ‘E’:

0, 1, 1, 0, 0

The functions would return the following:

| key | held | pressed | released | note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | F | F | F | ground |

| 1 | T | T | F | rising edge |

| 1 | T | F | F | continuing |

| 0 | F | F | T | falling edge |

| 0 | F | F | F | ground |

But how best to implement this?

The natural approach is to store the state of each key in a map:

type Keys struct { Held, Pressed, Released map[ebiten.Key]bool}

This isn’t a bad approach, but maps can be a little fiddly to access concurrently, and every access requires a pointer indirection and a hash lookup. We can do better.

Another approach is simply three arrays of bools:

type Keys struct { held, pressed, released [ebiten.KeyMax+1]bool} // +1 because ebiten.KeyMax is the highest key, not the number of keys; I think this is a bug in ebiten.

This is straightforward and requires no indirection, using a single byte per key - 327 bytes in total. But we can do better.

Actually, we don’t need 324 bits of information, since we can calculate Held(), Pressed(), and Released() by storing the electrical signal (0 or 1) for each key in the current frame and the previous frame and looking for rising and falling edges:

type Keys struct { thisFrame, lastFrame [ebiten.KeyMax+1]bool}

func (k Keys) Pressed(key ebiten.Key) bool {

return k.thisFrame[key] && !k.lastFrame[key]

}

func (k Keys) Held(key ebiten.Key) bool {

return k.thisFrame[key]

}

func (k Keys) Released(key ebiten.Key) bool {

return !k.thisFrame[key] && k.lastFrame[key]

}

That knocks us down to 218 bytes, but we can do better. Why store a bool for each key when we can store a single bit? We can use a bitset to store the state of each key by splitting the keys into two groups of 64 bits and do some bit twiddling to access them:

struct Keys {thisFrame, lastFrame struct { low, hi uint64 }}

func (k Keys) Held(key ebiten.Key) bool {

// read as: "check whether the key'th bit is set in thisFrame.low"

if key < 64 {

return k.thisFrame.low & (1 << key) != 0

}

// read as: "check whether the (key-64)th bit is set in thisFrame.hi"

key -= 64

return k.thisFrame.hi & (1 << key) != 0

}

func (k Keys) Pressed(key ebiten.Key) bool {

if key < 64 {

return k.thisFrame.low & (1 << key) != 0 && k.lastFrame.low & (1 << key) == 0

}

key -= 64

return k.thisFrame.hi & (1 << key) != 0 && k.lastFrame.hi & (1 << key) == 0

}

func (k Keys) Released(key ebiten.Key) bool {

if key < 64 {

return k.thisFrame.low & (1 << key) == 0 && k.lastFrame.low & (1 << key) != 0

}

key -= 64

return k.thisFrame.hi & (1 << key) == 0 && k.lastFrame.hi & (1 << key) != 0

}

With this design, we can store the state of every key on the keyboard in only 32 bytes (or four 64-bit words). This makes the input state small enough to cheaply copy wherever we need it. Additonally, if we ever needed to access it concurrently, we could use atomic operations to do so without any locks! Additionally, this opens up the possibility of using bit operations to enable or disable ‘groups’ of keys at once in very few instructions.

OK, that’s enough about the input API. Let’s get back to updating the terminal.

UpdateTerm()The following is an annotated version of the core of UpdateTerm(), stripping out some inessential features like clipboard support and saving the history to disk.

// Update the terminal state with the given input. If the user pressed enter, parse the current line and return a *Command.

//

// # cursor:

//

// ← and → move the cursor left and right

//

// ⇧ + ← and ⇧ + → move the cursor left and right a word

//

// # deletion

//

// ⌫ deletes the character to the left of the cursor

//

// ⇧ + ⌫ deletes a word to the left of the cursor

//

// ␡ deletes the character to the right of the cursor

//

// ⇧ + ␡ deletes a word to the right of the cursor

//

// # history:

//

// ↑ and ↓ navigate the history, if there is one: they don't wrap.

//

// ⇧ + ↑ and ⇧ + ↓ go to the start and end of the history.

func UpdateTerm(t *Terminal, keys input.Keys) (cmd *Command, err error) {

// bounds check the cursor & suggested completion, just in case

// we forgot to clean up after ourselves last frame

if !strings.HasPrefix(t.suggestedCompletion, t.curLine) {

t.suggestedCompletion = ""

}

t.cursor = util.Clamp(t.cursor, 0, len(t.curLine))

// how many navigation keys are pressed? if more than one, we do nothing rather than guess.

var (

up, down, left, right, backspace, del bool

shift = keys.Held(ebiten.KeyShift)

tab, enter = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyTab), keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyEnter)

)

if time.Since(t.lastNavigationRepeat) > time.Millisecond*200 {

up = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyUp) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyUp)

down = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyDown) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyDown)

left = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyLeft) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyLeft)

right = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyRight) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyRight)

backspace = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyBackspace) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyBackspace)

del = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyDelete) || keys.Held(ebiten.KeyDelete)

} else {

up = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyUp)

down = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyDown)

left = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyLeft)

right = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyRight)

backspace = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyBackspace)

del = keys.Pressed(ebiten.KeyDelete)

}

// how many navigation keys are pressed? if more than one, we do nothing rather than guess.

/* -- design note --

this is the most important part of this function, since it massively reduces the number of cases we need to handle. rather than worrying about what to do if the user presses both left and right, or if they both insert a character and delete a character, we just ignore those cases, assuming they're user error or bouncing keys.

the original design of this function was hundreds of lines longer and distinctly buggier. This is the fourth revision.

*/

b2i := func(b bool) int { if b { return 1 }; return 0 }

switch count := b2i(up) + b2i(down) + b2i(left) + b2i(right) + b2i(backspace) + b2i(del) + b2i(tab) + b2i(enter); count {

default: // more than one key pressed: do nothing

return nil, nil

case 0: // no navigation keys pressed: insert characters & adjust cursor position

t.curLineRunes = ebiten.AppendInputChars(t.curLineRunes[:0])

t.curLine = normalize(t.curLine[:t.cursor] + string(t.curLineRunes) + t.curLine[t.cursor:])

// adjust the cursor position for the new character(s)

t.cursor += len(t.curLineRunes)

t.cursor = max(t.cursor, 0)

t.cursor = min(t.cursor, len(t.curLine))

return

case 1:

t.lastNavigationRepeat = time.Now()

}

/* -- design note --

note that we check shift and also !shift. this is technically redundant, but it protects us against ordering bugs, since it means the switch cases are guaranteed to be mutually exclusive.

*/

switch {

default: // no navigation to do, like backspace on an empty line

return nil, nil

case enter: // execute the current line

line := t.curLine

t.curLine, t.cursor = "", 0 // reset the current line

c, err := ParseCommand(strings.Fields(line))

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// it's a valid command (in form, at least): add it to the history

const maxHistLen = 64

if len(t.history.Lines) >= maxHistLen { // trim the history:

// copy the back half of the history to the front

copy(t.history.Lines[:len(t.history.Lines)/2], t.history.Lines[len(t.history.Lines)/2:])

// then truncate the back half

t.history.Lines = t.history.Lines[:len(t.history.Lines)/2]

}

// now there's definitely room in the history

t.history.Index = len(t.history.Lines) - 1

t.history.Lines = append(t.history.Lines, line)

return &c, nil

case tab && t.suggestedCompletion != "": // autocomplete the current line

t.curLine = t.suggestedCompletion

t.cursor = len(t.curLine) // move the cursor to the end of the line

return nil, nil

case left && shift: // move cursor left a word

t.cursor = max(strings.LastIndexAny(t.curLine[:t.cursor], " \n"), 0)

return nil, nil

case right && shift: // move cursor right a word

if i := strings.IndexAny(t.curLine[t.cursor:], " \n"); i >= 0 {

t.cursor += i + 1

} else {

t.cursor = len(t.curLine)

}

return nil, nil

case left && !shift: // move cursor left.

t.cursor = max(t.cursor-1, 0)

return nil, nil

case right && !shift: // move cursor right

t.cursor = min(t.cursor+1, len(t.curLine))

return nil, nil

// --- deletion ---

case backspace && shift && t.cursor > 0: // delete word to the left

i := max(strings.LastIndexAny(t.curLine[:t.cursor], " \n"), 0)

t.curLine = t.curLine[:i] + t.curLine[t.cursor:]

t.cursor = i

return nil, nil

case backspace && !shift && t.cursor > 0: // delete char to the left

if t.cursor > 0 {

t.curLine = t.curLine[:t.cursor-1] + t.curLine[t.cursor:]

t.cursor--

}

return nil, nil

case del && shift && t.cursor < len(t.curLine): // delete word to the right

i := strings.IndexAny(t.curLine[t.cursor:], " \n")

if i < 0 {

i = len(t.curLine)

} else {

i += t.cursor

}

t.curLine = t.curLine[:t.cursor] + t.curLine[i:]

return nil, nil

case del && !shift && t.cursor < len(t.curLine): // delete char to the right

t.curLine = t.curLine[:t.cursor] + t.curLine[t.cursor+1:]

return nil, nil

// --- history navigation ---

case down && shift: // goto end of history

t.history.Index = len(t.history.Lines) - 1

t.curLine, t.cursor = t.history.Lines[t.history.Index], len(t.history.Lines[t.history.Index])

return nil, nil

case up && shift: // goto start of history

t.history.Index = 0

t.curLine, t.cursor = t.history.Lines[t.history.Index], len(t.history.Lines[t.history.Index])

return nil, nil

case up && !shift: // prev line in history

if t.history.Index--; t.history.Index < 0 {

t.history.Index = 0

}

t.curLine, t.cursor = t.history.Lines[t.history.Index], len(t.history.Lines[t.history.Index])

return nil, nil

case down && !shift: // next line in history

if t.history.Index++; t.history.Index >= len(t.history.Lines) {

t.history.Index = len(t.history.Lines) - 1

}

t.curLine, t.cursor = t.history.Lines[t.history.Index], len(t.history.Lines[t.history.Index])

return nil, nil

}

// unreachable

}

Our commands will have an OPCODE and zero or more ARGS. ARGS will be literals representing strings or numbers, (e.g. 100, hello)

, PATH to fields of the game state, or AUGOPs (augmented assignment operators) like += or *=.

PATHs will only be able to reach exported (i.e, capitalized) fields of the game state, respecting go’s usual rules for visibility. In order to make this easier to work with, all commands will be case-insensitive; in fact, we’ll lowercase them before parsing. This does allow for some ambiguities that could lead to ‘unreachable’ fields. If we had struct S {XY, xy int}, then s.xy would be ambiguous.

I resolve this problem by not making structs like that, but it’s worth noting this limitation.

| ITEM | description | example |

|---|---|---|

OPCODE |

specifies a console command | watch, mod, cpin |

PATH |

a path to a field of the game state. | player.hp, player.pos.x |

AUGOP |

an augmented assignment operator. | +=, *=, %= |

LITERAL |

a literal value, interpreted by the OP | 100, hello |

Commands will be of the form: OP arg1 arg2 ... argN, but we’ll also allow the form arg1 AUGOP arg2, which is equivalent to mod arg1 AUGOP arg2. (That is, mod is implied as the opcode.)

Some example commands:

| op | args | description |

|---|---|---|

watch |

watch player.hp |

add the player’s hp to the debug watch window |

cpin |

cpin player.hp 100 |

“reset the player’s HP to 100 every frame, “pinning it” to a constant value. |

mod |

mod player.hp = 100 |

set the player’s hp to 100 |

mod |

mod player.hp += 100 |

add 100 to the player’s hp |

mod |

player.x /= 2 |

halve the player’s x position; ‘mod’ is implied |

We’ll represent operators as an enum:

type OpCode int16 // operator. hard to imagine needing more than 256 operators, but we'll use 16 bits just in case.

const (

// Unknown or invalid operator

Unknown OpCode = iota

// WATCH adds a field to the debug watch window. Grammar: `watch <path>`

WATCH

// CPIN "pins" a field to a constant value, resetting it every frame. Grammar: `cpin <path> <path_or_literal>`

CPIN

// MOD modifies a field. Grammar: `mod <path> <augop> <path_or_literal>`, or <path> <augop> <path_or_literal>

MOD

)

Before we get to parsing, we have an important design decision to make: do we represent commands as a single struct regardless of opcode, or as a seperate struct for each command?

A single struct would look like this:

type Command struct {

Op Opcode

Args []string

}

func Exec[T any](pt *T, Command) (string, error) {

switch c.Op {

default:

return "", fmt.Errorf("unknown opcode %d", c.Op)

case Watch:

case Cpin:

case Mod:

}

}

Wheras a seperate struct for each command would look like this:

type Command interface {

Opcode() Op

Exec(reflect.Value) (string, error)

}

type Mod struct {

LHS, AugOp string

RHS reflect.Value

}

type Watch struct {

Path string

}

type Cpin struct {

Path string

Value reflect.Value

}

func (c Mod) Opcode() Op { return Mod }

func (c Mod) Exec(v reflect.Value) (string, error) {

// ...

}

func (c Watch) Opcode() Op { return Watch }

func (c Watch) Exec(v reflect.Value) (string, error) {

// ...

}

func (c Cpin) Opcode() Op { return Cpin }

func (c Cpin) Exec(v reflect.Value) (string, error) {

// ...

}

A single struct requires less code, but is ‘stringly typed’: we can’t use the type system to enforce that the arguments to mod are a path, an augop, and a path or literal. We’ll just have to make sure that Exec() does the right thing. As our list of commands grows, this may become more difficult to maintain, since we’ll have a “god switch” in Exec() that handles all commands.

A seperate struct for each command requires more code, but allows us to add new commands without touching the existing code. Additionally, once we have a parsed command, we have stronger guarantees about what it contains: we know that a Mod command has a Path, an AugOp, and a Value, and we can use the type system to enforce that.

A third, best option exists, but we can’t use it in Go. Languages with sum types (sometimes called “tagged unions” or “enums”) could express a Command like this:

// this is rust code: don't worry about it too much.

enum AugOp { Add, Sub, Mul, Div, Mod, Pow, BitAnd, BitOr, BitXor, BitClear, Shl, Shr }

enum Command {

Set(Path, Value),

Watch(Path),

Cpin(Path, Value),

AugAssign(path: Path, op: AugOp, value: Value),

}

This would combine the best of both worlds: we’d have a single type to represent all commands, but we could guarantee the proper structure of each.

Go doesn’t have sum types, so I chose the single struct approach to minimize the total amount of code.

Because we’re not using separate structs, I don’t do much validation in ParseCommand: instead, I’ll guarantee the bounds when we actually try and execute.

func ParseCommand(fields []string) (Command, error) {

switch op := strings.ToLower(fields[0]); op {

default: // unknown opcode

// is this an augmented assignment operator?

if len(fields) == 3 && augassignops[fields[1]] != nil {

return Command{MOD, fields[1:]}, nil

}

return Command{}, fmt.Errorf("unknown operation %q: expected one of %v", op, opNames)

case "mod":

if len(fields) != 4 {

return Command{}, fmt.Errorf("mod: expected 3 args")

}

return Command{MOD, fields[1:]}

case "cpin": // PIN a field to a Constant value

if len(fields) != 3 {

return Command{}, fmt.Errorf("cpin expects 2 arguments, got %d", len(fields)-1)

}

return Command{Op: CPIN, Key: fields[1], Vals: fields[2:]}, nil

/* other cases omitted; they're pretty similar. */

}

}

OK, easy enough. Now we get to the hard part: how do we implement Command.Exec()? That is, how do we access and modify arbitrary fields of arbitrary structs at runtime?

The reflect package allows you to operate on Go values of arbitrary type without knowing what type or types they are ahead of time. Reflect is too big of a subject to cover in detail here. Instead, I’ll first show a few examples of what you can do with it, then present a cheatsheet of the most useful types and functions for you to refer to, then we’ll get back to the console. If you’re completely lost, I recommend reading the reflect package docs and the reflect tutorial first. Chapter 12 of The Go Programming Language by Kernighan & Donovan is also an excellent resource: see the source code for that chapter’s examples here.

First, a few examples to get the idea across.

// https://go.dev/play/p/gh7TMf2-JlE

var f64type = reflect.TypeOf(0.0)

// get the value of "`X`" and "`Y`" fields of a struct, regardless of what type the struct is, as long as they're both _any_ numeric type, even if X or Y are embedded in another struct.

func getXY(v reflect.Value) (x, y float64, ok bool) {

if v.Type().Kind() != reflect.Struct { // make sure we have a struct

return 0, 0, false

}

// check if v.X or v.Y would be valid expressions at compile time on the type of v

vx, vy := v.FieldByName("X"), v.FieldByName("Y")

if !vx.IsValid() || !vy.IsValid() {

// they're not, so we can't do it at runtime either

return 0, 0, false

}

// and that f64(v.X) and f64(v.Y) would be valid conversions at compile time

if !vx.CanConvert(f64type) || !vy.CanConvert(f64type) {

// they're not, so we can't do it at runtime either

return 0, 0, false

}

// they are: convert them to float64s and return them

x, y = vx.Convert(f64type).Float(), vy.Convert(f64type).Float()

return x, y, true

}

IN:

func main() { // https://go.dev/play/p/IiMldZgkEum

for _, v := range []any{

&image.Point{1, 2}, // X and Y are `int` in this package!

&struct{ X, Y float64 }{3, 4},

&struct{ image.Point }{image.Point{5, 6}}, // embedded fields

} {

v := reflect.ValueOf(v).Elem() // get the Value of the pointer

x, y, _ := getXY(v) // get the value of the X and Y fields as float64s

fmt.Printf("%s: %v, %v\n", v.Type(), x, y)

}

}

OUT:

image.Point: 1, 2

struct { X float64; Y float64 }: 3, 4

struct { image.Point }: 5, 6

// https://go.dev/play/p/gh7TMf2-JlE

var f64type = reflect.TypeOf(0.0)

// set the value of the "`X`" and "`Y`" fields of a struct, so long as X and Y are both _any_ numeric type, even if X or Y are embedded in another struct.

// we could use this to, for example, set the position of an object in a game to the position of the mouse cursor.

func setXY(v reflect.Value, x, y float64) bool {

if v.Type().Kind() != reflect.Struct {

return false // not a struct

}

vx, vy := v.FieldByName("X"), v.FieldByName("Y")

if !vx.IsValid() || !vy.IsValid() {

return false // no X or Y field

}

if !vx.CanSet() || !vy.CanSet() {

return false // X or Y is unexported, part of an unexported struct, or isn't in an addressable struct

}

if !f64type.ConvertibleTo(vx.Type()) || !f64type.ConvertibleTo(vy.Type()) {

return false

}

vx.SetFloat(x)

vy.SetFloat(y)

}

```go

// https://go.dev/play/p/gh7TMf2-JlE

func main(){

for _, v := range []any{

&image.Point{1, 2}, // X and Y are `int` in this package!

&struct{ X, Y float64 }{3, 4},

&struct{ image.Point }{image.Point{5, 6}},

} {

v := reflect.ValueOf(v).Elem() // get the Value of the pointer

x, y, _ := getXY(v) // get the value of the X and Y fields as float64s

fmt.Printf("%s: %v", v.Type(), v.Interface()) // print the type and the values

setXY(v, x*10, y*10) // set the value of the X and Y fields to 10x their original value

fmt.Printf("-> %v\n", v.Interface()) // print the type and the values

}

}

```

OUT:

```text

image.Point: (1,2)-> (10,20)

struct { X float64; Y float64 }: {3 4}-> {30 40}

struct { image.Point }: (5,6)-> (50,60)

```

// zero out the given field of a struct, regardless of the type of struct or field, or whether the field is embedded in another struct.

func zeroField(v reflect.Value, fieldName string) bool {

if v.Type().Kind() != reflect.Struct {

return false // not a struct

}

f := v.FieldByName(fieldName)

if !f.IsValid() {

return false // no field

}

if !f.CanSet() {

return false // field is unexported, part of an unexported struct, or isn't in an addressable struct

}

f.Set(reflect.Zero(f.Type()))

return true

}

IN:

// https://go.dev/play/p/YO8LmQqqZuJ

func main() {

type A struct{ F string }

var a = A{"foo"}

fmt.Printf("a: before: %+v\n", a)

zeroField(reflect.ValueOf(&a).Elem(), "F")

fmt.Printf("a: after: %+v\n", a)

type B struct{ F int }

var b = B{2}

fmt.Printf("b: before: %+v\n", b)

zeroField(reflect.ValueOf(&b).Elem(), "F")

fmt.Printf("b: after: %+v\n", b)

}

OUT:

a: before: {F:foo}

a: after: {F:}

b: before: {F:2}

b: after: {F:0}

Reflect operates on three main types: reflect.Type, reflect.Value, and reflect.Kind. reflect.Type represents a type, reflect.Value represents a value of that type, and reflect.Kind represents the underlying primitive type of a reflect.Type; that is, something like int, string, struct, map, slice, etc.

Get a Value from a normal variable via reflect.ValueOf(t), then modify it with the various functions on reflect.Value. Pretty much anything you can do in ‘ordinary’ go you can do with some combination of reflect.Value’s methods. E.g, the following snippets are functionally equivalent:

var n int

reflect.ValueOf(&n).Elem().SetInt(50)

func main() {var n int; *(&n) = 50}

Or to show it another way:

reflect.ValueOf(&n). // &

Elem(). // *

SetInt(50) // =

Note the pointers. Since reflect.ValueOf is an ordinary function, you’ll need to pass a pointer if you want to modify one of the arguments, just like any other function.

Find out information about a type via reflect.TypeOf(t) or the underlying primitive type via Type.Kind().

In the following notation, eleme t is a reflect.Type, v is a reflect.Value, T and B is are types, and t and b are values of those types (not reflect.Values, but the normal type you get via ':=', 'var', etc.

Here’s a quick cheatsheet of the types and functions we’ll use in this article. Feel free to skip this for now, and come back to it when or if you need it.

| shorthand | type | obtained via |

|---|---|---|

| v | reflect.Value |

reflect.ValueOf("some string") |

| t | reflect.Type |

v.Type() or reflect.TypeOf("another string") |

| k | reflect.Kind |

t.Kind() |

| f | reflect.StructField |

t.Field() or t.FieldByName() or t.FieldByNameFunc() |

| n | int8..=int64 or int |

n := 2 |

| b | bool |

b := true |

| s | string or struct |

s := "some string", s := struct{foo int}{"foo} |

| m | map |

m := map[string]int{"a": 1} |

| a | slice or array |

a := []int{1, 2, 3} |

| function | description | example | analogous to |

ValueOf |

get a Value from an ordinary value |

reflect.ValueOf(int(2)) |

t := 2 |

||

TypeOf |

get a Type from the value |

t := reflect.TypeOf(int(2)) |

int |

||

| Type.Kind | get the underlying primitive type | t.Kind() |

int |

||

| — | — | — | — | ||

Type.ConvertibleTo |

can the type be converted to a different type? | t.ConvertibleTo(reflect.TypeOf(0)) |

|||

Value.Addr |

get the address of a value | v.Addr() |

&t |

||

Value.CanAddr |

can the value be addressed? | v.CanAddr() |

|||

Value.CanConvert |

can the value be converted to a different type? | v.CanConvert(reflect.TypeOf(0)) |

|||

Value.Convert |

convert a value to a different type | reflect.ValueOf(&t).Elem().Convert(reflect.TypeOf(b)) |

T(v) |

use | |

Value.Elem |

dereference a pointer or interface | v.Elem() |

*t |

||

Value.Field |

get the nth field of a struct |

v.Field(0) |

|||

Value.FieldByName |

for struct kinds, get the field with the given name |

v.FieldByName("someField") |

t.someField |

||

Value.FieldByNameFunc |

for struct kinds, get the field with the given name, matching the given predicate |

v.FieldByNameFunc(func(s string) bool { return strings.EqualFold(s, "somefield") }) |

s.someField or s.somefield or s.Somefield |

||

Value.Index |

for array and slice kinds, get the nth element |

v.Index(0) |

a[0] |

||

Value.Interface |

get an ordinary value back from a Value (as any) |

reflect.ValueOf(2).Interface().(int) |

any(int(2)).(int) |

||

Value.Len |

for array, map, and slice kinds, get the length |

v.Len() |

len(a), len(m) |

||

Value.MapIndex |

for map kinds, get the value associated with the given key |

v.MapIndex(reflect.ValueOf("someKey")) |

m["someKey"] |

||

Value.Set |

set lhs to rhs, if they’re the same Type |

v.Set(reflect.ValueOf(2)) |

t = 2 |

OK, that covers what we’ll need for now. Let’s get back to the console.

In order to execute commands, we’ll need to be able to:

We’d like a function which allows us to access any of the subfields of the Game struct, regardless of how deeply nested they are.

That is, we’d like a function like this:

// FollowPath follows a path of '.'-separated keys through a struct, map, or slice, returning the value at the end of the path.

// pointers and interfaces will be continually dereferenced.

func ResolvePath[T any](pt *T, path string) (reflect.Value, error) {}

type Inner struct{ X int }

type Outer struct{ Inner Inner }

type S struct{ Outer Outer }

var s = S{Outer: Outer{Inner: Inner{X: 1}}}

ResolvePath(&s, "outer.inner.x") // like reflect.ValueOf(&s.outer.inner.x).Elem()

Additionally, we’d like a single uniform syntax that allows us to access fields of structs, indices of slices or arrays, and values of maps. Taking a cue from lua, we’ll use . as our access operator. All of these should work:

type S struct{ N int, A []map[string]int }

func printResolved[T any](pt *T, path string) {

v, err := ResolvePath(pt, path)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Printf("%s: %v\n", path, v.Interface())

}

func main() {

s = S{N: 1, A: []map[string]int{{"a": 1}, {"1", 3}}}

printResolved(&s, "n") // 1

printResolved(&s, "a.0") // map[string]int{"0": 3}

printResolved(&s, "a.0.a") // 1

printResolved(&s, "a.1.0") // 3: note that 0 is treated as a string here, since that's the type of the keys of the map.

printResolved(&s, "a.1.-1") // 3: negative indices for slices are treated as python or FORTRAN-style negative indices, where -1 is the last element, -2 is the second-to-last, etc.

}

Let’s walk through our implementation of ResolvePath step by step. First, we’ll need a few helper functions: derefVal to dereference pointers and interfaces, and normalize to unify our path syntax.

// continually dereference pointers and interfaces until we get a non-pointer, non-interface value.

// panic if we dereference more than 32 times, since this means we've hit some kind of self-referential loop.

func derefVal(v reflect.Value) reflect.Value {

for i := 0; v.Kind() == reflect.Ptr || v.Kind() == reflect.Interface; i++ {

v = v.Elem()

if i > 32 {

panic("dereferenced 32 pointers, but still got a pointer or interface")

}

}

return v

}

// whitespaceUnifier replaces all whitespace with a single space.

var whitespaceUnifier = strings.NewReplacer("\t", " ", "\n", " ", "\r", " ")

// normalize normalizes a string by

// - lowercasing it

// - replacing all whitespace with a single space

// - removing leading and trailing whitespace

// warning: given the implementation of normalize, we will not be able to access some string map keys.

// this may not be appropriate for your use case. Again, I solve this problem by "not doing that".

func normalize(s string) string {

s = strings.ToLower(s)

s = strings.TrimSpace(s)

old := s

for {

s = whitespaceUnifier.Replace(s)

if s == old {

return s

}

old = s

}

}

Our outside-facing API will take the .-separated path:

func func ResolvePath[T any](pt *T, path string) (reflect.Value, error) {

return resolvePath(reflect.ValueOf(pt).Elem(), strings.Split(path, "."))

}

And our implementation will step through the path, following each key in turn:

// follow a path of key, case-insensitively, through a struct, map, or slice, returning the value at the end of the path.

// pointers and interfaces will be continually dereferenced.

//

// type S struct{ F struct { A [3]int } }

// s := S{F: struct{ [3]int }{[3]int{42, 43, 44}}}

// v, _ := followPath(reflect.ValueOf(s), "f", "a", "0")

// fmt.Println(v)

// Output: 42

func followPath(root reflect.Value, keys ...string) (reflect.Value, error) {

v := derefVal(root) // will be updated once per loop iteration

for i, field := range keys { // follow the path: e.g, player.pos.x

t := v.Type()

switch k := t.Kind(); k {

default:

return v, fmt.Errorf("%s: %v is not a struct, map, slice, or array", root.Type(), strings.Join(keys[:i+1], "."))

// structs are simple: just get the field by (normalized) name.

case reflect.Struct:

v = v.FieldByNameFunc(func(s string) bool { return normalize(s) == field })

if !v.IsValid() { // field not found

return v, fmt.Errorf("%s: %v has no field %q", root.Type(), strings.Join(keys[:i+1], "."), field)

}

case reflect.Slice, reflect.Array:

// treat the key as an integer index. we use strconv.ParseInt to allow users to use hex, binary, or octal indices if they'd like.

j64, err := strconv.ParseInt(field, 0, 0)

j := int(j64)

if err != nil {

return v, fmt.Errorf("%s: %v is not a valid index", root.Type(), strings.Join(keys[:i+1], "."))

}

if j < 0 {

j += v.Len() // python-style negative indexing; -1 is the last element, -2 is the second-to-last, etc.

// but don't allow silly things like -1000 if the slice only has 3 elements.

}

if j < 0 || j >= v.Len() {

return v, fmt.Errorf("%s: index %d out of bounds", root.Type(), j) // out of bounds

}

v = v.Index(j)

}

case reflect.Map:

// treat the key as a map key.

// separate branches for uints, ints, floats, strings.

// all other types are not supported.

var key any

var err error

// treat theis field as a map key, parsing it as losslessly as possible into the highest-precision numeric Kind we can.

// i.e, uint8..64 => uint64, int8..64 => int64, float32 => float64, string => string

switch t.Key().Kind() {

case reflect.String:

key, err = field, nil

case reflect.Int, reflect.Int8, reflect.Int16, reflect.Int32, reflect.Int64:

key, err = strconv.ParseInt(field, 0, 64)

case reflect.Uint, reflect.Uint8, reflect.Uint16, reflect.Uint32, reflect.Uint64, reflect.Uintptr:

key, err = strconv.ParseUint(field, 0, 64)

case reflect.Float32, reflect.Float64:

key, err = strconv.ParseFloat(field, 64)

default:

err = fmt.Errorf("%s: %v is not a supported map key type", root.Type(), strings.Join(keys[:i+1], "."))

}

if err != nil {

return v, fmt.Errorf("%s: %v is not a valid map key: failed to parse as %v: %w", root.Type(), strings.Join(keys[:i+1], "."), t.Key().Kind(), err)

}

// convert the key to actual type of the map's key and use it to index the map.

// this handles both precision (e.g, uint64 -> uint8) and custom types (e.g, type Celsius float64 -> float64).

// more about this in the next section.

key = reflect.ValueOf(key).Convert(t.Key())

// now index the map

v = v.MapIndex(key)

}

return derefVal(v), nil

}

We’d like all of the following commands to work, without worrying about the type of the fields or the values: they should “just work”:

set player.hp 100set player.hp 100.0set player.hp player.xset player.pos npcs.0.posAdditionally, we’d like the ability to handle custom types, like colors

How to handle literals depends on the type of the field we’re setting.

strconv.ParseBool.encoding.TextUnmarshaler interface, which is implemented by many types in the standard library, including *time.Time and net.IP. A note here: most of the time, these types require a pointer for the method, so we might occasionally need to add a level of indirection to satisfy the interface. This will have the highest priority. While it is possible for a type to implement encoding.TextUnmarshaler without a pointer receiver (some maps, for example), we will omit this case. After all, this console doesn’t need to solve all problems, just the problems I have.Additionally, we’d like to handle one last case - the color.RGBA struct is already in use throughout the codebase. I could surround it with a wrapper that implements encoding.TextUnmarshaler to make the syntax uniform, or I can special-case an exception. Here, I choose to special-case the exception. I find myself doing this more than once, though, I might consider adding wrappers rather than making the code too complicated.

Let’s see what this looks like in code:

// https://go.dev/play/p/KzqjgzF1PhP

// SetString interprets src as a string literal, and attempts to set dst to that value.

// Conversions happen in this order:

// If dst, &dst, *dst, **dst, etc implement encoding.TextUnmarshaler, use UnmarshalText([]byte(src))

// Otherwise, if dst is a string, set it to src.

// Otherwise, if dst is a bool, set it to the result of strconv.ParseBool(src)

// Otherwise, if dst is a numeric type, set it to the result of strconv.ParseFloat(src, 64).

func SetString(dst reflect.Value, src string) error {

// special cases: do dst, &dst, *dst, **dst, etc implement encoding.TextUnmarshaler?

if dst.CanAddr() {

if x, ok := st.Addr().Interface().(encoding.TextUnmarshaler); ok != nil {

return x.UnmarshalText([]byte(src))

}

}

// keep dereferencing until we get a non-pointer, non-interface value, trying to satisfy the TextUnmarshaler interface on the way.

for i := 0; dst.Kind() == reflect.Ptr || dst.Kind() == reflect.Interface; i++ {

if x, ok := dst.Interface().(encoding.TextUnmarshaler); ok != nil {

return x.UnmarshalText([]byte(src))

}

dst = dst.Elem()

if i > 32 {

panic("dereferenced 32 pointers, but still got a pointer or interface: self-referential loop?")

}

}

/* design note:

this took a lot of iteration to condense to a reasonable amount of code.

early designs had separate cases for uint8, uint16, etc.

later designs converted all numerics to a float64 intermediate, then converted to the final type,

but I was unsatisfied with the loss of precision and inability to use hex or binary literals (`0xFF`, `0b1010`).

In this design, we use the ability to assign all of the results of Parse[Bool|Int|Uint|Float] to an `interface{}` (the 'any' type)

to greatly simplify the code, since Reflect.ValueOf takes an interface{} anyway.

*/

var x any // value to set dst to

var err error

switch dst.Kind() {

default:

err = fmt.Errorf("cannot convert %s to %s", src, dst.Type())

case reflect.String:

x = src

case reflect.Bool:

x, err = strconv.ParseBool(src)

case reflect.Int, reflect.Int8, reflect.Int16, reflect.Int32, reflect.Int64:

x, err = strconv.ParseInt(src, 0, dst.Type().Bits())

case reflect.Uint, reflect.Uint8, reflect.Uint16, reflect.Uint32, reflect.Uint64, reflect.Uintptr:

x, err = strconv.ParseUint(src, 0, dst.Type().Bits())

case reflect.Float32, reflect.Float64:

x, err = strconv.ParseFloat(src, dst.Type().Bits())

}

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("cannot convert %s to %s: %w", src, dst.Type(), err)

}

dst.Set(reflect.ValueOf(x).Convert(dst.Type()))

return nil

}

Let’s try it out on each of our cases:

func main() {

// https://go.dev/play/p/TPUf33CWQhT

ip := new(net.IP) // implements encoding.TextUnmarshaler

if err := SetString(reflect.ValueOf(ip), "192.168.1.1"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(ip) // 192.168.1.1

n := 0

if err := SetString(reflect.ValueOf(&n), "22"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(n) // 22

s := "foo"

if err := SetString(reflect.ValueOf(&s), "somestring"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(s) // somestring

b := false

if err := SetString(reflect.ValueOf(&b), "true"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(b) // true

c := color.RGBA{} // special case

if err := SetString(reflect.ValueOf(&c), "0xFF000000"); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println(c)

}

OUT:

192.168.1.1

22

somestring

true

{255 0 0 0}

Seems good. Let’s handle paths.

Paths are slightly more complicated. We need to resolve the path, and then convert the value at the end of the path to the correct type. Unlike literals, we don’t want to ‘stringly type’, but we would like to allow for go’s usual type conversions, such as int32 to float64 or []byte to string. reflect.Value.Convert and reflect.Value.CanConvert will do this for us.

We’ve already written resolvePath, so let’s write a function to convert the value at the end of a path:

// Set the value of dst to the value of src. If src is not convertible to dst, return an error.

func SetVal(dst, src reflect.Value) error {

dst, src = deref(dst), deref(src)

if src.ConvertibleTo(dst.Type()) {

lhs.Set(rhs.Convert(dst.Type()))

return nil

}

return fmt.Errorf("cannot convert %s to %s", src.Type(), dst.Type())

}

We can use this to implement the = operator:

// set the value at the end of the path to the value of the literal or path.

// litOrSrcPath is always a literal if quoted: otherwise, it's a path.

func set(root reflect.Value, dstPath, litOrSrcPath string) error {

dst, err := ResolvePath(root, dstPath)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if strings.HasPrefix(litOrSrcPath, `"`) && strings.HasSuffix(litOrSrcPath, `"`) {

// definitely a literal. we need to parse it into the correct type.

// we'll use the type of the lhs as a guide.

return SetString(dst, litOrSrcPath[1:len(litOrSrcPath)-1])

}

// not a literal. maybe it's a path?

src, pathErr := ResolvePath(root, litOrSrcPath)

if pathErr == nil {

return SetVal(dst, src)

}

// maybe it's a literal, and thats why we couldn't resolve it as a path?

if litErr := SetString(dst, litOrSrcPath); litErr != nil {

// not a literal either

return fmt.Errorf("set %s %s: %s not a path, and could not be parsed as a literal: %w", dstPath, litOrSrcPath, litErr)

}

return SetVal(dst, src)

}

We now have everything we need to execute commands. Let’s implement the first command, MOD, allowing for operators:

func Exec[T any](pt *T, cmd Command) (description string, err error) {

defer func() {

// the console should never panic, even if the command is invalid.

// if it does, we'll recover and return an error.

if r := recover(); r != nil {

err = fmt.Errorf("panic: %v", r)

}

}()

switch c.Op {

case MOD:

f, ok := binop[cmd.Args[0]] // a table of functions for each operator: get to this in a second

if !ok {

return "", fmt.Errorf("unknown operator %q", cmd.Args[0])

}

if cmd.Args[0] == "=" {

err := set(reflect.ValueOf(pt).Elem(), cmd.Args[1], cmd.Args[2])

return fmt.Sprintf("set %s = %s", cmd.Args[1], cmd.Args[2]), err

}

dst := reflect.ValueOf(pt).Elem()

/*

--- design note: ----

the choice to use only float64s here loses some precision.

for integer types. I've gone back and forth on this, but in the end I think this is OK: for integer types <=32 bits it will be

exact, and human beings are unlikely to do arithmetic on integers >32 bits in the console.

still, maybe I'll change my mind later.

---

*/

// augmented assignment operators only make sense for numeric types. we treat as float64s to simplify implementation.

rhsVal := reflect.ValueOf(new(float64)).Elem() // addressable float64

set(rhsVal, "", cmd.Args[2]) // set rhs to the value of the literal or path, converting if necessary.

rhs := rhsVal.Float()

var lhs float64

switch k := dst.Type().Kind(); k {

default:

return "", fmt.Errorf("cannot use augmented assignment operator on %s: kind %s", dst.Type(), k)

case reflect.Int, reflect.Int8, reflect.Int16, reflect.Int32, reflect.Int64:

lhs = float64(dst.Int())

case reflect.Uint, reflect.Uint8, reflect.Uint16, reflect.Uint32, reflect.Uint64, reflect.Uintptr:

lhs = float64(dst.Uint())

case reflect.Float32, reflect.Float64:

lhs = dst.Float()

}

res := f(lhs, rhs)

SetVal(dst, reflect.ValueOf(res))

}

}

The promised operator table:

var binop = map[string]func(f64, f64) f64{

"-=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return a - b },

"*=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return a * b },

"/=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return a / b }, // division: div by zero will panic, but that's OK: it will get caught by the panic handler

"&=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(uint64(a) & uint64(b)) }, // loses some bits of precision

"%=": func(a, b f64) f64 {

if a < b {

return math.Mod(a, b) + b // math.Mod(-1, 8) == -1, but we want 7

}

return math.Mod(a, b)

}, // euclidean mod: not sign-preserving

"**=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return math.Pow(a, b) }, // exponentiation

"&^=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(uint64(a) &^ uint64(b)) }, // clear bits, losing some precision

"^=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(int(a) ^ int(b)) }, // bitwise xor

"+=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return a + b }, // addition

"<<=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(int(a) << uint64(b)) }, // sign-preserving left shift

"=": func(_, b f64) f64 { return b }, // assignment

">>=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(int(a) >> uint(b)) }, // sign-preserving right shift, losing some precision

"|=": func(a, b f64) f64 { return f64(int(a) | int(b)) }, // bitwise or, losing some precision

}

We can easily add new commands by adding new cases to the switch statement. PRINT seems like an obvious choice:

case PRINT:

v, err := ResolvePath(reflect.ValueOf(pt).Elem(), cmd.Args[0])

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return fmt.Sprintf("%s: %v", cmd.Args[0], v.Interface()), nil

And many more exist in the real codebase. Right now, the current list of commands and their usage strings are:

// examples of each op, printed by the help command.

examples = validate.MustNonZero("examples", [OP_N][]string{

CALL: {"<TODO>"},

CONCATLOAD: {`concatload npcs hitsquad`, "concatload walls maze"},

CPIN: {`cpin player.HP 9999999`},

DESTROY: {"destroy all", "destroy npcs"},

ENV: {"env PATH"},

FLATWATCH: {`flatwatch player`},

FOLLOWMOUSE: {"followmouse player", "followmouse ui.watchlist", "followmouse"},

HELP: {"help", "help MOD"},

LIST: {"list patterns", "list ops", "list saves"},

LOAD: {"load player.x player_x.json"},

MOD: {`mod player.x *= 10`, `mod player.x -= player.y`, `player.x *= 10`},

PRINT: {"print player.x"},

RESTART: {"restart"},

RPIN: {`rpin player.HP 9999999`},

SAVE: {"save player.x player_x.json"},

SET: {"set player.x 150"},

SETMOUSE: {"setmouse player"},

TOGGLE: {"toggle ui.ammo.enabled"},

UNPIN: {`unpin player.HP`, `unpin player.HP player.x`, "unpin all"},

UNWATCH: {"unwatch"},

WATCH: {"watch player.y"},

})

// usage strings for each op, printed by the help command.

usage = validate.MustNonZero("usage", [OP_N]string{

CALL: "call <key> [args...]",

CONCATLOAD: "concatload <walls|npcs|pickups> file",

DESTROY: "destroy pickups|npcs|walls|all",

ENV: "env [key]",

FLATWATCH: "flatwatch <key> [format]", // todo: recurse into structs to customizable depth???

HELP: "help",

FOLLOWMOUSE: `followmouse [key]`,

LIST: "list [patterns|saves|ops]",

LOAD: "load <key> <file.json>",

CPIN: "cpin <literal>",

RPIN: "rpin <key>",

MOD: "mod <key> <op> <numeric_lit | key>",

PRINT: "print <key> [format]",

RESTART: "restart",

SAVE: "save <key> <file.json>",

SET: "set <key> <value>",

UNPIN: "unpin <all> | unpin [key0] [key1] ...",

SETMOUSE: "setmouse <key>",

TOGGLE: "toggle <key>",

UNWATCH: "unwatch",

WATCH: "watch <key> [format]",

})

// opnames for each op, used for autocomplete and help.

opNames = validate.MustNonZero("opnames", [OP_N]string{

CALL: "call",

DESTROY: "destroy",

ENV: "env",

CONCATLOAD: "concatload",

FLATWATCH: "flatwatch",

FOLLOWMOUSE: "followmouse",

HELP: "help",

LIST: "list",

LOAD: "load",

CPIN: "cpin",

RPIN: "rpin",

TOGGLE: "toggle",

MOD: "mod",

PRINT: "print",

SAVE: "save",

RESTART: "restart",

UNPIN: "unpin",

SET: "set",

SETMOUSE: "setmouse",

UNWATCH: "unwatch",

WATCH: "watch",

})

see a previous article, go quirks & tricks pt 3, for more info on validate.MustNonZero

This covers the basics of how to build a console

There’s still plenty more to cover, like

followmouse: a command that allows you to ‘drag’ any UI element, enemy, or object around the screen with your mouse.flatwatch: a live debug windowAnd I’d love to go into the tradeoffs of alternative designs, like embedding a LUA interpreter instead.

But this article is more than long enough already (pushing nearly 10000 words!). I’ll save those for next time.

Like this article? Need help making great software, or just want to save a couple hundred thousand dollars on your cloud bill? Hire me, or bring me in to consult. Professional enquiries at efron.dev@gmail.com or linkedin

The reflect package tries only to expose operations that are valid in ‘normal’ go. Normal rules about type-safety and visibility are respected where possible. Sometimes you need to do something drastic, like directly modify an unexported field or field of unexported (possibly unknown) type!

Any addressable value of known size (that is, native go values with a known location in memory) can be set to an arbitrary byte pattern at runtime. Please do not do this unless you are absolutely sure you both

The basic idea is this: we use the tools of reflect to find the address of the field we want to modify. We then convert both that address (the “destination” address) to byte slices of equal length using unsafe.Slice. We then do a raw copy of the bytes from the source to the destination.

This doesn’t so much subvert Go’s type system as break it over its knee. It is your job to maintain all the invariants of the type system. You won’t even get friendly panics if you mess up: at best you’ll get a segfault: at worst, anything could happen.

Let’s demonstrate:

// https://go.dev/play/p/eZLxNfFBfeV

func main() {

var s S

func() { // this guy panics as follows:

// reflect: reflect.Value.SetInt using value obtained using unexported field

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

log.Println(r)

}

}()

reflect.ValueOf(&s).Elem().FieldByName("n").SetInt(2)

}()

fmt.Println(s)

// but this does not:

src := 2

dst := reflect.ValueOf(&s).Elem().FieldByName("n")

copy(

// take the address of the source: reinterpret it as a slice

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), dst.Type().Size()),

// take the address of the source: reinterpret it

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(&src)), unsafe.Sizeof(src)), //

)

fmt.Println(s)

}

We can restate this as a general-purpose function, using generics to make sure our source at least is an addressable value of known size and protecting ourselves against size mismatches:

// https://go.dev/play/p/eZLxNfFBfeV

// SetUnsafe sets the value of dst to the value of src, without obeying the usual rules about

// type conversions, field & type visibility, etc. Go wild.

// dst must be an addressable Value with a type that is the same size as src.

func SetUnsafe[T any](dst reflect.Value, src *T) {

size := unsafe.Sizeof(*src)

if size != dst.Type().Size() {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("cannot set %v (size %d) to %v (size %d)", src, size, dst.Type(), dst.Type().Size()))

}

copy(

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), int(size)),

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(src)), int(size)),

)

}

What if we already have a slice of bytes? That’s simpler: just omit the mainpulation of src:

// https://go.dev/play/p/eZLxNfFBfeV

// SetUnsafeBytes sets the value of dst to the value of src, without obeying the usual rules about type conversions, field & type visibility, etc.

// dst must be an addressable Value with a type that is the same size as the length of src (but it DOESN'T have to be conventionally settable).

//len(src) must be equal to the size of dst, or it will panic.

func SetUnsafeBytes(dst reflect.Value, src []byte) {

if uintptr(len(src)) != dst.Type().Size() {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("cannot set %v (size %d) via slice of len %d", dst.Type(), dst.Type().Size(), len(src)))

}

copy(

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), len(src)),

src,

)

}

There’s one last corner case I want to mention: suppose src is a reflect.Value already? If src is addressable, we can just use the same technique on src as we do on dst: if it’s not, we’ll have to copy src to a temporary value which is addressable. See example:

func SetUnsafeValue(dst, src reflect.Value) {

// https://go.dev/play/p/eZLxNfFBfeV

if src.Type().Size() != dst.Type().Size() {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("cannot set %v (size %d) to %v (size %d)", src, src.Type().Size(), dst.Type(), dst.Type().Size()))

}

if !src.CanAddr() {

// we can't take the address of src, so we'll have to copy it to something which _is_ addressable.

src2 := reflect.New(src.Type()).Elem() // reflect.New creates a pointer to a new zero value of the given type... so it's elem is addressable.

src2.Set(src) // we can safely set the value of src2 to the value of src, since they're the same type.

src = src2 // and now src is addressable.

}

// nothing we can do about dst not being addressable, though: we'll simply panic.

copy(

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), int(dst.Type().Size())),

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(src.Addr().UnsafePointer()), int(src.Type().Size())),

)

}

// SetUnsafe sets the value of dst to the value of src, without obeying the usual rules about

// type conversions, field & type visibility, etc. Go wild.

// dst must be an addressable Value with a type that is the same size as src.

func SetUnsafe[T any](dst reflect.Value, src *T) {

size := unsafe.Sizeof(*src)

if size != dst.Type().Size() {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("cannot set %v (size %d) to %v (size %d)", src, size, dst.Type(), dst.Type().Size()))

}

copy(

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), int(size)),

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(src)), int(size)),

)

}

// SetUnsafeBytes sets the value of dst to the value of src, without obeying the usual rules about type conversions, field & type visibility, etc.

// dst must be an addressable Value with a type that is the same size as the length of src (but it DOESN'T have to be conventionally settable).

//len(src) must be equal to the size of dst, or it will panic.

func SetUnsafeBytes(dst reflect.Value, src []byte) {

if uintptr(len(src)) != dst.Type().Size() {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("cannot set %v (size %d) via slice of len %d", dst.Type(), dst.Type().Size(), len(src)))

}

copy(

unsafe.Slice((*byte)(dst.Addr().UnsafePointer()), len(src)),

src,

)

}